By Alan Weisman

Thirty years ago, Homelands was funded by the Ford Foundation to do a series for National Public Radio called Searching for Solutions. We were to travel the world looking for ways to grow food sustainably, develop green cities, address overpopulation, et cetera. I drew the clean energy assignment, and soon became interested in hydrogen, which burns like natural gas, except its only exhaust is water vapor. It seemed important, but the material I was finding was pretty technical, always tricky with radio.

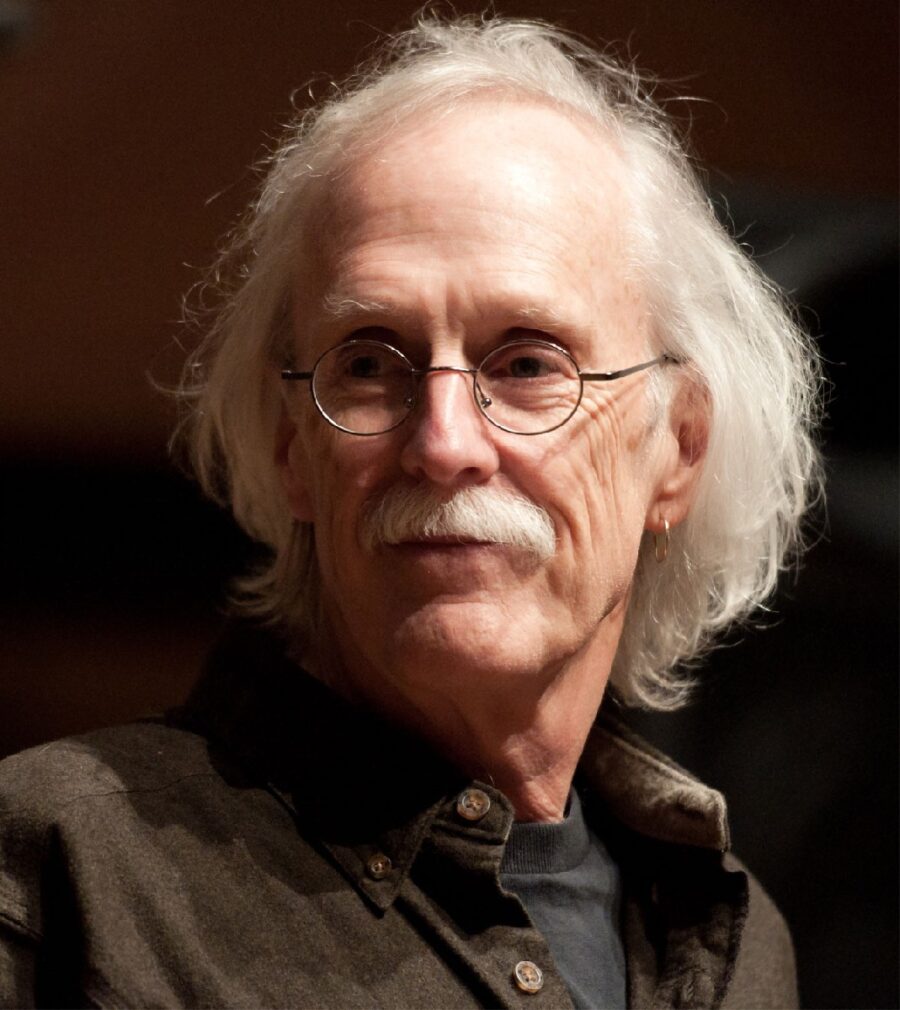

“Why not ask Chris Brookes to collaborate with you?” suggested my Homelands colleague Cecilia Vaisman. “He even made chaos theory work for radio,” she said in awe.

We were all awed by Chris, a freelance radio producer from Newfoundland. When I first signed on to work with Cecilia and our colleague Sandy Tolan, I was a print reporter who’d never done radio, so they handed me a stack of Chris Brookes tapes, from coverage of war in El Salvador to hurdy-gurdy builders in Amsterdam to, yes, chaos theory. It wasn’t just his unerring ear and fine reporting: his writing, timing, and whimsical delivery were so imaginative, so musical, that you just had to keep listening. I recall one night when we raced to a dinner appointment while playing his latest astonishing piece, about the crash of the Georges Bank cod fishery. When we pulled into the parking ramp, even though we were late, we couldn’t move — we could barely breathe — until it was over.

Chris’s training, I later learned, was in theater: he’d studied at the Yale School of Drama, and founded a company, The Mummers Troupe, that traveled Canada for years, until a gig at the CBC introduced him to radio. I called him at his home studio in St. John’s. “Hydrogen? I know utterly nothing about it.”

“I know some.” Germany, I told him, was in the research forefront, with both Daimler Benz and BMW working on hydrogen-powered cars. “But I don’t know how to turn it into listenable audio.”

“If you can handle the knowledge part, I can do the other.”

We met in the Frankfurt airport, got a rental car, and drove to Stuttgart. Our initial interviews were at the Max Planck Institute and a university in Ulm. Soon our heads were drowning in engineering jargon, and we had hours of useless tape. After three days, Chris was so glazed that when we saw a poster for a production of Goethe’s Faust, he said he needed a theater fix, bad. “It’s in German,” I pointed out.

“So what? I haven’t understood a thing all week.”

I accompanied him. Five long, incomprehensible acts. When Faust was being dragged down to hell in the final scene, it felt like the punishment we deserved for blowing this story. But Chris did something that wouldn’t have occurred to me: he started recording.

During the next week we toured Daimler, BMW, and drove through the Black Forest to see a hydrogen-powered house at an institute in Freiburg. That gave Chris an idea. Freiburg was near the village where Goethe’s inspiration, an alchemist named Dr. Faustus, had died when one of his experiments exploded in a cloud of sulfur fumes. We went and actually located his house, but on that quiet street there wasn’t much to record. Chris insisted on hanging around. When the town clock struck midnight, I announced I was going to bed. “I’m going to wait a little while longer,” said Chris.

To hear what his microphone found when his patience ultimately paid off, go to The Great Hydrogen Car Race. First, you should know this: The Monday after we flew home, I called him to brainstorm a script. “It’s already done,” he told me. Not only that, he was already mixing it. I was simultaneously miffed that my writing apparently wasn’t indispensable, and vastly relieved, because I had scant idea what to do with the dense material we’d gathered. He sent us a tape. We listened. We sent it to NPR, which rejected it unless we were willing to make severe cuts, because it was a half-hour long. “Not a chance,” said Sandy Tolan, our executive producer. He sent it to Marketplace. Their producers agreed it was so amazing that they blew out their entire half-hour format and ran it intact as an Earth Day special.

Chris and I also on collaborated on a story we reported together in south Texas and northeastern Mexico, Laguna Madre, and on Gaviotas, a piece I reported in Colombia for All Things Considered, which he co-wrote and edited and Sandy Tolan produced. Thanks greatly to him, it was rebroadcast both on The Best of NPR and on Living on Earth — and I’m doubly in his debt, because a few days after it first aired, a publisher offered me a book contract.

But you want to hear Chris’s own incomparable work, which you can find at Battery Radio. Rather than recommend individual pieces, because this wouldn’t end, I’ll simply say that Chris Brookes was considered such a national treasure that in 2000 he received the Order of Canada: the Canadian equivalent of knighthood. Pick any story of his and listen. You won’t stop.

On April 10, Chris died in an accidental fall at his home. He is survived by his wife, also a Newfoundland treasure, cellist and traditional fiddler Christina Smith, and mourned by all of us who will never stop hearing him in our hearts and heads, challenging us always to make it better than we thought possible.

Read an obituary of Chris Brookes on the CBC website.

Listen to more Homelands stories by Chris:

Newfoundland Shipwreck Survivor